Thomas Cubitt was a very remarkable man: outstanding builder of the nineteenth century, innovative developer of property, and friend of royalty. Nicknamed “Emperor of the Building Trade”, the former journeyman carpenter made a vast fortune from good business principles and craftsmanship. Yet he always thought of the welfare of his workmen and of the people, rich or poor, who would live in his houses.

Thomas Cubitt was a very remarkable man: outstanding builder of the nineteenth century, innovative developer of property, and friend of royalty. Nicknamed “Emperor of the Building Trade”, the former journeyman carpenter made a vast fortune from good business principles and craftsmanship. Yet he always thought of the welfare of his workmen and of the people, rich or poor, who would live in his houses.

His main connection with Ranmore Common is his 1850 purchase of the Denbies Estate, superbly set on top of the North Downs and overlooking the small town of Dorking. Denbies was the adjacent estate to Polesden Lacey; in 1821-3 he had rebuilt that house for Joseph Bonsor (who had purchased the dilapidated property from the son of the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan).

When Thomas bought Denbies House, it was a modest 18th century country dwelling, but in his view it needed improvements, more effective sanitation, and better communication with the railway station. He therefore designed a massive replacement on the top of the hill, visible for miles around. He planted thousands of trees and shrubs, started to modernise the Estate and farm buildings, and improve the land, much of which his son George had to finish after Thomas died in 1855.

“The House on the Hill” (Ranmore Archive)

EARLY YEARS

St Andrew’s Buxton, where several Cubitt children were baptised (Geograph, copyright John Salmon)

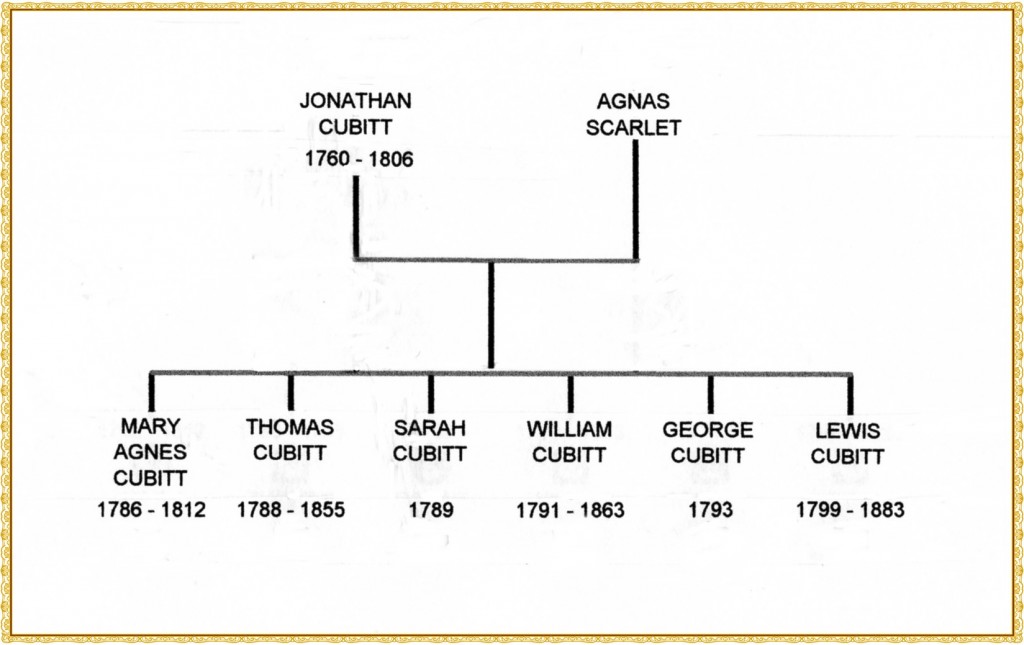

Thomas Cubitt was baptised 25th February 1788 at St Andrew’s Church, Buxton, a little village near Norwich, Norfolk. His parents Jonathan Cubitt (descended from yeoman farmers) and Agnes nee Scarlet(t) had other children, the eldest being Mary Agnes (later Cuthell ) baptised at Buxton on 7th July 1786, as was her younger sister Sarah on 30th August 1789. Then came three brothers: William baptised Norwich on 17th April 1791, George baptised 10th February 1793 at St Nicholas, Great Yarmouth, and finally Lewis born in London 1799.

It has not been possible to follow all the siblings forward. It is not known what happened to Sarah; George was apparently lost at sea; but the three surviving brothers had notable careers in building and architecture. William Cubitt worked with Thomas as a pupil and subsequent partner before setting up on his own. He built Cubitt Town in East London, and became Lord Mayor of London in 1860 and 1861. Lewis Cubitt started off as a partner to his brothers, but later set up his own architect practice: his most notable structures were the Great Northern railway terminus and its adjacent hotel at Kings Cross in London. More details on William, Lewis and Mary Agnes, whose son Andrew Cuthell became Thomas’s right hand man, are on their respective pages.

The Cubitt family had apparently moved to London by 1799 when Lewis was born. There is a tradition that the father Jonathan worked as a carpenter, and maybe Thomas worked with him. Jonathan is believed to have died in 1806, leaving his wife and children in poverty (although in 1803 an “Agnas Cubitt” was buried in Clerkenwell, London, so she may have predeceased him). Thomas only escaped destitution by signing on as a carpenter on a ship sailing for India. He managed to salt away enough money from the voyage that, returning to London at the age of 21, he could set himself up as a master carpenter in Holborn. Reroofing the Russell Institution was his first major job, completed so speedily and satisfactorily that more jobs followed.

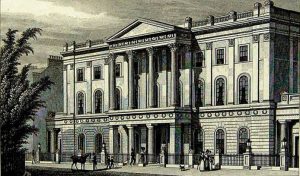

The London Institution, “an elegant stone structure … with a noble library, reading-rooms, a lecture room … approached by a noble staircase” (engraving by William Deeble, via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1815 the 27-year-old Thomas was given the prestigious but taxing commission to build a new headquarters for the London Institution in Moorfields (which promoted “the diffusion of Science, Literature and the Arts”, the building eventually being subsumed into London University, though it was demolished in 1936). The contract had very severe penalty clauses if Thomas did not complete on time, and this decided him to take the innovative step for which he is famous: of employing the whole workforce as a “one stop shop”, rather than following the then current practice of subcontacting out the work to other trades, often unreliable, inefficient and slow. He engaged a complete staff of building tradesmen, each gang working under an experienced foreman. He did not care much for working under architects, so he subsequently set up a surveying and drawing office. Eventually, he even set up his own nurseries for planting the gardens of his Squares and those of the individual houses he built.

EXPANDING THE BUSINESS

Entrance to Cubitts building yard on Gray’s Inn Road, now demolished (London Metropolitan Archives)

Initially, Thomas and his two brothers worked together. To provide workshops for their much increased team of 250 workers, they took premises in Gray’s Inn Road, and the years 1816 to 1821 were ones of general prosperity and of steady expansion of the business. On the whole, they concentrated on contracts rather than speculative building, although Thomas also took land on the Calthorpe estate adjacent to his yard for his first speculative developments, probably in order to find continuous work for his men.

However, in 1825 he started negotiations for the enormous and risky speculations on which his great fortune was based. He was a tough but fair negotiator, and took many parcels of land, notably on the Grosvenor and Lowndes Estates, to create a great swathe of buildings centred on Belgrave Square. He had an unrivalled ability to fit numerous pieces of ground, of all shapes and sizes and all kinds of conditions, into a grand design, and to prepare the ground uniformly for building.

The particularly admired north side of Eaton Square typifying the Thomas Cubitt style of building (Geograph, copyright Paul Leonard)

About 1000 men worked on the Belgravia project, laying out and constructing sewers and drains, pavements, street lighting, roads for access, broad streets, spacious squares and whole districts. The north and west sides of Eaton Square exemplify the Cubitt style – classical Greek or Italianate. His skill in building and public relations was such that it attracted the wealthy and, a mere thirty years after he started, “the richest population in the world” was the description of Belgravia.

But even when he built more modest homes, Thomas maintained his standards: streets are as spacious as possible, and area railings and other ironwork are to the same high specification as elsewhere. Waterclosets were installed as standard in all his buildings, even in stables and coachhouses. Indeed, “Cubitt” is still a magic word when Victorian terrace housing is bought and sold.

Neethouse Gardens in 1812, later developed by Thomas Cubitt as South Belgravia or Pimlico (image copyright Westminster City Archives)

Thomas also took marshy land in an area called Neethouses south of Belgravia, previously used for market gardening, but liable to flooding from a local sewer and the Thames at high tide. He raised the ground level with 150,000 barge-loads of earth, constructed an embankment (paying for much of it himself) , and built housing for the expanding business class of London in what is now known as Pimlico.

Thereafter, he was working almost at the same time in Belgravia, Bloomsbury, North London, Clapham and Brighton. Both his brother William and his bankers were alarmed by his daring, and only his enormous energy and great financial acumen carried through his more ambitious schemes, especially when the building industry was assailed by depression in the late 1820s and 1830s. However, Thomas always laid off part of his risk by a series of clever deals. His partnership with William was dissolved in 1827, but brother Lewis stayed on for a few more years before rejoining William in 1831.

In the 1930s, with Thomas Cubitt long gone, two-thirds of the vast Thames Bank site was used for building Dolphin Square, another project conceived on a grand scale in the Cubitt tradition, but, of course, not by his organisation. This “high class” modern residential complex, complete with shops and other facilities, was at the time the largest block of flats in Europe: 1,310 apartments for around 3,000 people (photograph by Matt S from London, uploaded to Wikimedia by France3470 , licensed for reuse under Creative Commons).

THE WORKS AT THAMES BANK

From 1839-1843 Thomas built a new complex of workshops and a draw dock (a lined and gated inlet off the river) on an eleven-acre site at Thames Bank: long ranges of workshops, an engine house with an elegant Italianate chimney, and much stabling. Using the latest steam-driven technology, his works produced joinery, glass, plasterwork, steel and marble, as well as some of the bricks and cement for his various building operations.

Boats and lighters brought materials round by sea and up the Thames to his wharves: York stone paving, clay for brickmaking, gravel, stone chippings and “rubbish” (hardcore) for roadways, Purbeck stone, Welsh slates, plate glass from Sunderland, bricks from a number of Cubitt brickyards around London and Aylesford in Kent, as well as hay and straw for his horses.

No 3 Lyall Street, Belgravia, site of Thomas Cubitt’s blue plaque (by Spudgun67, Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

The great strength of Thomas Cubitt was that his men had experience of both workshops and office. He split his complex office organisation into three sections (law business, the general office of “builders clerks” managed by his nephew Andrew Cuthell, and finance department).

As well as working from Thames Bank, for 20 years Thomas moved his office around, using a completed house (often in Eaton Place) while he was developing the surrounding area. From 1846 until his death he worked from No 3 Lyall Street (which now boasts his blue plaque).

As well as working from Thames Bank, for 20 years Thomas moved his office around, using a completed house (often in Eaton Place) while he was developing the surrounding area. From 1846 until his death he worked from No 3 Lyall Street (which now boasts his blue plaque).

MARRIAGE AND CHILDREN

Thomas Cubitt had married Mary Anne Warner on 25th March 1821 at St Marylebone, and they produced a large family: Anne (born c 1820), Mary (1821), Emily (1823), George , later 1st Lord Ashcombe (1828), Sophia (1830), Fanny (1832), William (1834), Lucy (1835), Caroline (1837), Arthur (1840), and the twins Thomas and Charles (1842).

Lincoln House, Thomas Cubitt’s house in Clarence Road, Clapham Park (reproduced by permission of London Borough of Lambeth, Archives Department)

In 1825 Thomas leased 225 acres outside London in Clapham, to develop into a smart suburb of villas for City merchants, with large gardens and stabling. At once he started to build himself a large house in Clarence Road (Lincoln House, demolished 1905). Here he chose to live and bring up his children, his son George being the first to be born in Clapham. The house was set among 22 acres of grounds, two entrances each with its own lodge, a 100-yard-long drive, paddocks and a lake.

Lewes Crescent, Brighton, part of Thomas Cubitt’s development (image courtesy of Linda Jackson copyright 2013, Epsom and Ewell Local History Explorer)

OUTSIDE LONDON

Brighton had by now superseded Bath as the out-of-season resort for London society, and from the mid 1820s Thomas built houses there (apparently, the only ones on which he ever lost money). He involved himself in and then carried on developing Kemp Town. From time to time he lived in the house he built at No 13 Lewes Crescent, popular with Mrs Cubitt and the family. The German Spa waters were supposed to benefit his rheumatism.

ROYAL CONNECTIONS

Thomas Cubitt was now quite wealthy and beginning to move in higher circles. An introduction to Prince Albert produced a commission to modify Osborne House on the Isle of Wight to house Albert and Queen Victoria’s ever-increasing family. Then, working with the Prince, he rebuilt the house in Italianate style, spending five years on the project and renting a house there, half the rent being paid by the Queen. He persuaded Prince Albert not to use Cubitt men to build cottages, saying the project would provide work for local people. The Queen and Prince Consort thought very highly of him, and Victoria described him as “Our Cubitt”. Indeed, she was so fond of him that twenty-five years after his death, when his son George was made a member of the Privy Council, she wrote in her journal, “The son of our dear old Mr Cubitt who built Osborne”.

Osborne House, Isle of Wight (Geograph, copyright Philip Halling)

After Osborne, Thomas constructed the new east (front) wing to Buckingham Palace from the design of the architect Edward Blore, although he still did not like working under architects. He was also unhappy about the choice of Caen Stone, which decayed so rapidly under London soot that large chunks fell away after a very few years, and the whole east front had to be replaced in 1913. He was characteristically forthright in his terms – that is my price, no tendering – but he basked in the confidence of Prince Albert and the Queen. In the end, the Buckingham Palace project gave him more prestige than profit, although he never complained about this.

An engraving of Buckingham Palace in 1837, showing John Nash’s Marble Arch before Cubitt built the East Front.

To make room for the new wing of the Palace, Thomas dismantled, and then re-erected at Cumberland Gate, the splendid Marble Arch designed by John Nash as the ceremonial entrance to Buckingham Palace. He later constructed the south wing of the Palace, with a Ballroom. He interested Prince Albert in the Great Exhibition of 1851; after its success, he negotiated the purchase of land in South Kensington as a permanent memorial to the Exhibition (the Museums, Imperial College and the Albert Hall), an area now known as Albertopolis.

WORKING FOR THE COMMON GOOD

With such royal connections Thomas Cubitt’s advice was asked on many projects and he gave evidence to various Commissions and parliamentary bodies. He tried to prevent the ill effects of smoke issuing from large steam chimneys and, appalled at the state of London’s foul sewers, in 1843 he proposed a method for improving the drainage in which can be seen the bare bones of the scheme carried out by Joseph Bazalgette after 1858.

Chelsea Embnkment between the River Thames and Battersea Park today (Geograph, copyright Danny P Robinson)

Thomas supported charitable projects and churches. He also suggested amenities for the general public. He was particularly keen on open spaces: he built an embankment to the south of the River Thames, and encouraged the setting up of Battersea Park, offering to fund much of both.

Unlike many employers of his time, he showed consideration for his men, many of whom he regarded as his friends. His workshops were designed for their comfort and convenience (large, lofty, well heated and ventilated). Each workshop had an area for cooking, as well as a high rail under the roof to dry coats after a wet walk to work. He established a workman’s library for his men, set up evening classes for his apprentices, and a school for his workmen’s children. However, he was very strict with those who drank or gambled, supplying soup and cocoa to the men to break them of the habit of dram-drinking. Not everyone approved of his attitudes, but he asserted, “If you wait till people thank you for doing anything for them, you will never do anything. It is right for me to do it, whether they are thankful for it or not.”

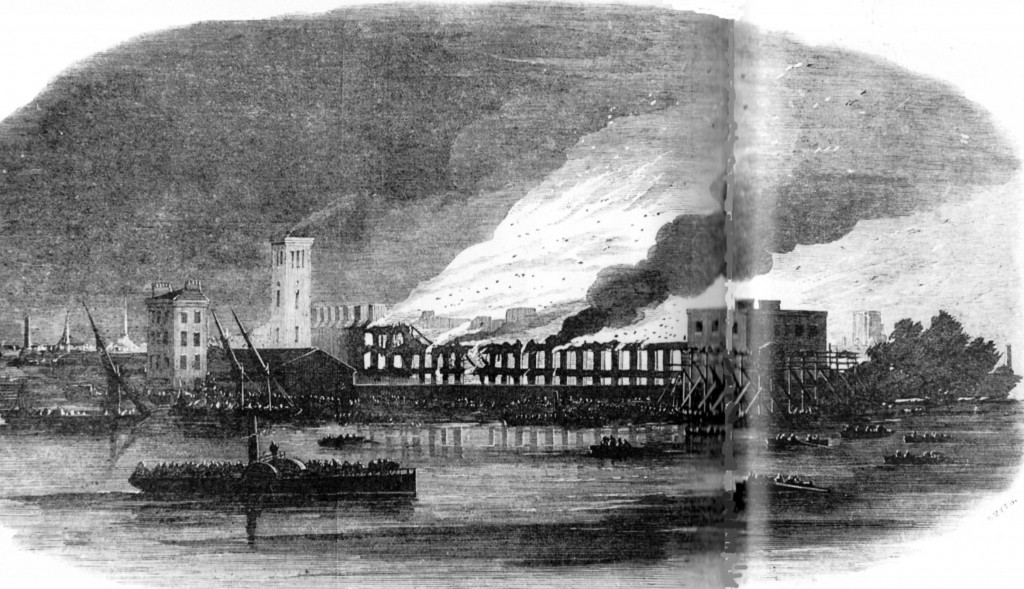

His care for his workmen was specially demonstrated when, in 1854, his premises at Thames Bank burned down with 30,000 pounds’ damage (most embarrassing because of a contract for new floors for the Buckingham Palace ballroom and the Crimson Drawing Room at Windsor). Despite much damage and uncooperative insurers, his first words were, “Tell the men they shall be at work within the week, and I will subscribe £600 towards buying them new tools.”

THE FINAL YEARS

During the last five years of his life Thomas tried to decrease his commitments as a developer and contractor, and to purchase a country estate at Denbies near Dorking, probably as much for his eldest son George as for himself. He divided his time between Denbies, Brighton and Clapham, as well as making occasional visits to Osborne. Travel to London from Surrey at the beginning of the railway age was such that he could take an express train from Dorking (now Dorking Town) at 9.55 am, arrive at London Bridge at 10.45, and leave again at 4.30 pm. The time from Brighton to London was also about 50 minutes, but he complained to his daughter Lucy that 100 minutes took a large chunk out of his day.

The Cubitt monument at Norwood, plot 649, square 48 (photograph courtesy of Julia&Keld (Find a Grave)

Sadly, Thomas did not enjoy his new house at Denbies for long, dying there from throat cancer on 20th December 1855. He was buried in the cemetery at West Norwood in a brick vault under a ten-ton granite slab (now a Grade II listed building) ringed by a holly hedge. The grave also contains the remains of some of his children, several of whom predeceased him, including two who died within two days of each other.

Statue of Thomas Cubitt in Dorking (Geograph, copyright Martyn Davies)

His was the longest will ever filed at Somerset House (386 folios of 90 words each and covering 30 skins of parchment). His estate was worth over a million pounds (a vast fortune for the time), probate duty £15,000. Denbies was left to his widow Mary Anne for life (she survived him by 25 years) and then to male heirs in succession. The first of these was his son George Cubitt (later lst Baron Ashcombe) who greatly extended the Denbies Estate and built St Barnabas Church.

Since Thomas Cubitt is responsible for many of the grand white stucco houses in Belgravia and Pimlico, it is appropriate that Pimlico has a monument to him (at the bottom of Denbigh Street), and there is a copy of this statue in Dorking. Several London restaurants and pubs have been named after him.

In 1883 the Cubitt business was acquired by Holland & Hannen, a leading competitor, becoming Holland, Hannen & Cubitts. Over the years the combined business constructed many important buildings, including the Cunard Building in Liverpool, London County Hall, Unilever House, the Royal Festival Hall, the Roxburgh Dam in New Zealand and the Trawsfynydd power station in North Wales. The firm was eventually integrated into Tarmac Construction.

The Cenotaph in Whitehall, London, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens. The original was built by Holland, Hannen and Cubitts (Photograph by Godot13, Wikimedia licensed under Creative Commons)

Possibly the most poignant of the firm’s building projects, in view of the deaths in WW1 of three of Thomas’s great grandsons, was the Cenotaph in Whitehall, a tall plinth topped by an empty casket (“Cenotaph” is Greek for “empty tomb”); unveiled on 11th November 1920, the day the Unknown Warrior was buried in Westminster Abbey.

However, despite the high regard in which Thomas Cubitt was held by both the Queen and Prince Albert, and the reputed offer of a title for his services at Buckingham Palace and Osborne, he died plain “Mr Cubitt” (unlike his brother William who was knighted). Long afterwards, the Queen, explaining to Gladstone why she was reluctant to confer a peerage on a financier, mentioned Thomas Cubitt and George Stephenson as men who “would have done honour to any House of Peers”. There is a legend that Thomas refused a title, or perhaps he was never officially honoured because he died before the magnificent new South wing at Buckingham Palace was finished. Whatever the truth of the matter, “The Builder” magazine’s obituary described him as a “great builder and a good man”, an accolade that might well have pleased him the most.

With all his great wealth and undoubted influence, he remained humane and considerate to his employees, practical and modest in dealing with his customers, respected for his consideration and integrity. Among all the tributes to him, perhaps the most telling is that of Queen Victoria. In her diary for Christmas Eve 1855, just after his death, she wrote, “In his sphere of life, with the immense business he had in hand, he is a real national loss. A better, kindhearted or more simple, unassuming man never breathed… We feel we owe much to him for the way he carried out everything.”

A right royal tribute indeed

Copyright©2016

SOURCES

This is a composite list of the sources consulted for Thomas Cubitt and all members of his family (including his siblings William Cubitt and Lewis Cubitt), but details for the individual family members are available if required. Most of the sources mentioned can be viewed online via Ancestry, Find My Past and Free BMD.

Birth, marriage and death registers and certificates, General Register Office (GRO)

Baptism. marriage, burial registers, St Andrew’s Buxton, St Marylebone, Holy Trinity Clapham, St Mary Magdalene (parish of St Pancras), St Andrew Holborn, St Pancras, South Metropolitan Cemetery, London Metropolitan Archives (LMA); St Barnabas Ranmore Common, Surrey History Centre (SHC)

Censuses 1841-1911, The National Archives (TNA)

London Marriages and Banns 1754-1921 (LMA)

London and Surrey Marriage Bonds and Allegations, 1597-1921 (LMA)

National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1858-1966 (Principal Probate Registry)

Post Office Directory (various years), UK City and County Directories 1600-1900s

Cambridge University Alumni, 1261-1900, Cambridge University Press

London, England, Freedom of the City Admission Papers, 1681-1925 (LMA)

Dictionary of National Biography (DNB)

Grace’s Guides: British Industrial History (http://www.gracesguide.co.uk)

“Thomas Cubitt, Master Builder”, Hermione Hobhouse, Macmillan London1971, reissued Management Books Ltd 1991. The definitive biography to which these pages are much indebted

“The House on the Hill, The Story of Ranmore and Denbies”, S.E.D. Fortescue, Denbies Wine Estate, 1993. A very valuable account

“Man and Boy”, Sir Stephen Tallents, Faber and Faber, 1943. Contains a fascinating chapter describing Denbies Mansion built and furnished by his great grandfather Thomas Cubitt

St Barnabas School logbook (SHC)

FOR MORE ON THOMAS CUBITT’S WIFE AND CHILDREN